Dr. Marcos Moscoso-Garay, former PhD Student of Hispanic Studies, explores how the stereotyping of Amazonian women by novelists and filmmakers of the 20th and 21st centuries undermined the effectiveness of their criticism towards capitalist extractivist production during the Amazon Rubber Boom (Part 1). He also shares about his graduate student experience at UBC (Part 2).

Marcos Moscoso-Garay and his daughter on the Amazon River.

“The purpose of my research is to show the ways in which industrial modernization, and the modes and relations of capitalist extractivist production, helped to perpetuate stereotypes about gender and nature in the Amazon.”

Part 1: Research

What is your research topic?

My research examines the representation of women during the Amazon Rubber Boom in the work of novelists and filmmakers of the 20th and 21st centuries. The purpose of my research is to show the ways in which industrial modernization, and the modes and relations of capitalist extractivist production, helped to perpetuate stereotypes about gender and nature in the Amazon.

The Amazon Rubber Boom

The Amazon Rubber Boom had its splendor approximately between 1879 and 1914, a historical moment of world expansion of an industrial-type capitalism undertaken by countries with imperialist characteristics such as England, Germany, France or the United States. It is also the time where new national states in Latin America started delimited borders.

Since the time of rubber extraction, Amazonia has become a space for ideological struggle. In the literature that I analyze, I find that the main objective of some writers (the majority) is to criticize the neo-colonialist system and its consequences. For a few other authors (the minority), their objective is to demonstrate the benefits of the industrialization of the Amazon, even at the cost of its ecological impact and the extermination of some populations.

In my research, I investigate how these artists under study—like Jaime Mendoza, Lino La Rosa Olazábal and Alberto Vázquez Figueroa—react to, problematize, and criticize the discourse of progress, the hope in capital, and the systematic process of death, torture and slavery against indigenous women during the time of rubber extraction. I argue that their attempted criticism of the system is not effective, however, because it is mediated by a discourse of modernity that keeps stereotyping Amazonian women by using the metaphor of the ‘machine/automaton’ woman, and nature as a utopian place of endless wealth.

Stereotyping Amazonian Women

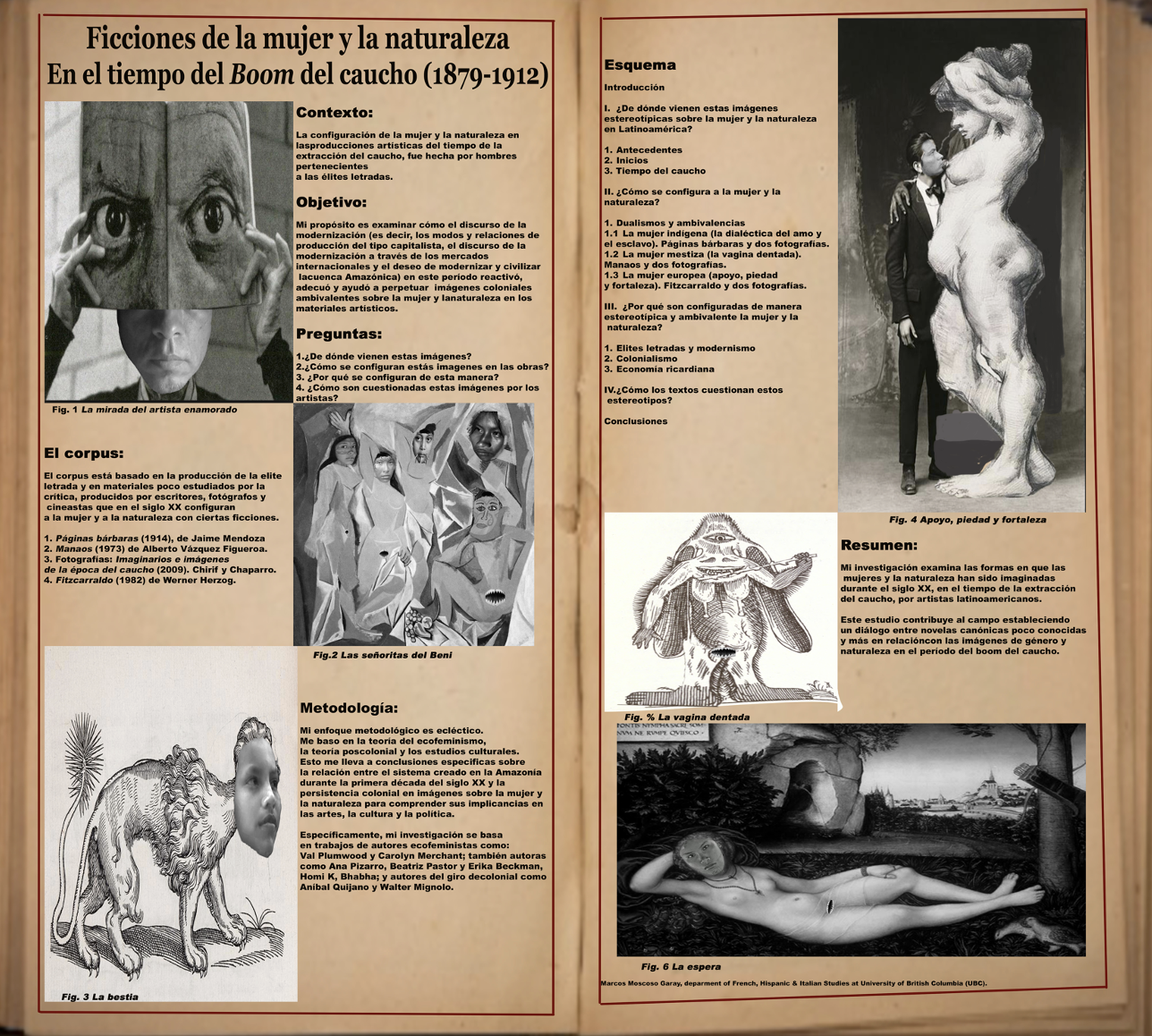

Research poster by Marcos that was awarded one of the Best Graduate Posters in French and Hispanic Studies (2018).

Portrayals of the Amazon in Latin American literature tend to fixate upon gender and nature (and the relationship between them). They demonstrate the stereotyped and idealized way in which Amazonian women and nature have been understood. I show how the female character of the Amazonian woman has been simplified to a kind of object (machine/automaton) by the artists who intend to criticize the system created in the time of rubber extraction.

I study eleven novels written across the 20th and 21st centuries, emphasizing one in each chapter: Páginas bárbaras (1914), Los Shiringeros (1965) and Manaos (1973). These works take the reader back to the time of rubber exploitation from different perspectives, demonstrating a literary system created in relation to long-lasting stereotypes. These novels also highlight the ambivalence of these stereotypes about women and nature, both of which are portrayed as beautiful and sensual, but also dangerous and wild. In some cases (Mendoza, for instance), writers try to re-evaluate Amazonian cultures, re-articulating these stereotypes in a positive fashion. In other cases (Rivera and Vargas Llosa), women and nature are simply condemned to ever-lasting ambivalence.

My research explores the following questions:

- What are the articulated images of women and the Amazon in these works and which ones are repeated with more insistence?

- Where do these images about women and nature come from?

- How are these metaphors reviewed in relation to the system implemented at the time?

- Also, is there an interest, in these works, to criticize the system of the capitalist, colonialist and patriarchal type and vindicate the Amazonian cultures?

Because several of these works were written many years after the Rubber Boom period, I maintain that these novels are a kind of laboratory to think about a variety of themes—such as civilization and barbarism; nature and culture; Amazonian modernity; political leadership; the role of women and men in that modernity; utopias of the Amazonía (modern cities and heterosexual families); the figure of the ‘machine woman’ and ‘automation’ in the representation of Amazonian women—among other themes.

Part 2: Graduate Student Experience

Centro de Estudios Teológicos de la Amazonía. A library in Iquitos within the Peruvian Amazon where Marcos spent some time working on his PhD thesis.

“I chose to study at UBC because it is a top-rated institution. My program has a select group of professors with a very good reputation.”

Why did you choose UBC as the university to pursue your studies?

I chose to study at UBC because it is a top-rated institution. In addition, my program has a select group of professors with a very good reputation. I was particularly excited to study in depth Latin American literature, art, history and philosophy. I am profoundly grateful for all that I have learned in the Department of French, Hispanic and Italian Studies.

What was it like working with your graduate supervisor?

Dr. Kim Beauchesne is my graduate supervisor. She has been a boundless fount of support, comprehension, and generosity throughout my academic career. From the beginning, she let me find my own voice. She was always available and attentive to my progress. With her suggestions and her corrections, she always tried to make sure that my work met high academic standards. I have learned a lot from her way of working and will always be grateful to her.

I also want to mention the members of my thesis committee, Dr. Alessandra Santos and Dr. Jon Beasley-Murray. I am deeply grateful to them for their firmness and generosity, and for all of their valuable comments on my research. I have learned a lot from their suggestions.

What advice would you give to those who are discerning whether graduate school is for them?

I could only answer this question with a poem by the Spanish poet Antonio Machado. “Caminante no hay camino se hace camino al andar…”

In English:

“Traveler, your footprints

are the only road, nothing else.

Traveler, there is no road;

you make your own path as you walk.

As you walk, you make your own road,

and when you look back

you see the path

you will never travel again.

Traveler, there is no road;

only a ship’s wake on the sea”.

Apply to our Graduate Programs

If you are interested in pursuing a MA or PhD in French or Hispanic Studies, we are currently accepting applications for the September 2023 and January 2024 intakes. Apply by December 31, 2022.