“Tiempo del sur tells the story of a family through the voices of four women: Manuela, Titi, Elena and Elisa. Each of them, from their point of view, reveals the events that over the years have marked their path in several countries—Colombia, the United States and Canada—and the particular effect that those events have had on their lives and personalities. The novel creates a vivid and harmonious mosaic of female voices that is able to show both the character and feelings of the four protagonists and how they interconnect in family relationships. Through the four protagonists, the reader can explore different ways of facing experiences such as illegal immigration, homosexuality, death and love.” – Sandra Barrriales Bouche, McGill University

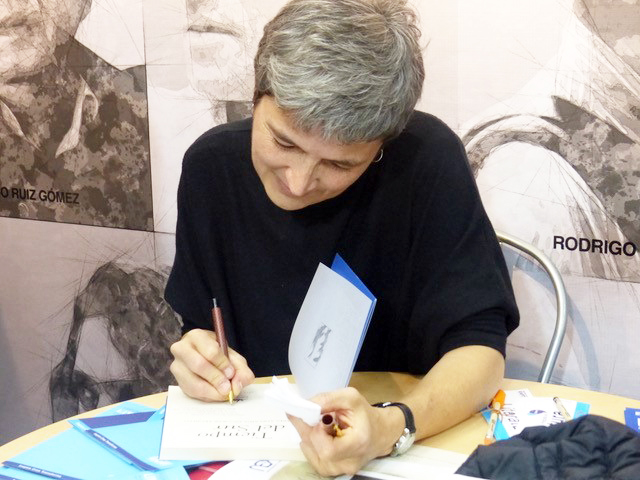

Dr. María Adelaida Escobar-Trujillo, Sessional Lecturer of Spanish, shares the inspiration behind her first fiction novel Tiempo del sur.

“Writing this novel helped me say serious things—political statements that might be dangerous to say in other contexts—through different voices. This is the freedom of creative writing.”

The city I grew up in, Medellín, Colombia, was a very violent city. Drug cartels, narcos, guerrilla conflict—all of this was part of my reality. Since I was a child, my friends were killed for narcos; I even experienced bombs in my own house. I couldn’t meet new people without being asked if I was related to Pablo Escobar. They say that in order to hate something, you need to know it first … and I hated this.

My book is called Tiempo del sur because it is about characters who return to Colombia after migrating up north to escape these realities, only to find that the situation they left back home has remained the same—people are still poor, there are few opportunities, everything is still expensive and the government is still corrupt—although the characters, themselves, have changed. That’s what this book is: a critique about a very violent and conservative city that is resistant to change.

But at the same time, each character in my novel still speaks with so much love for their city. I tried to show that even though you criticize your city, it’s still a part of you. This is what you love. This is who you are—your roots. This book is my way of saying “thank you” to the places that have made me who I am. For this reason, I wanted to publish the book in my home city of Medellín.

Immigration Issues

This book is particularly relevant in the historical moment we are living in. Not only does it relate to the immigration issue in the United States, but also to immigrants going from Venezuela to Colombia, or from Syria to other parts of the world. It’s so difficult to get legal status. You need to be a student, a qualified worker, or to have a huge bank account, which just isn’t an option for middle-class or poor families.

I’ve read many novels about illegal immigrants, but this one is different because it’s about well-educated, middle-class immigrants who left their countries with legal status, but decided to stay in the new country as illegals after their visas expired. This book is my way of saying to society, “What are you doing with these people? They need to leave their countries, but the borders are closed right now.” It’s important to have compassion for others, and I hope the book helps in this way.

Book launch of Tiempo del sur at Fiesta del Libro y la Cultura in Medallín, Colombia.

Homosexuality and Female Voices

The first day I launched my book in Colombia, a teenage girl came up to me and asked, “Is it true that your novel is about two women who get married? Do you really think it’s possible for people to live like that?” When I answered, “Yes,” she paused for a moment and said, “Thank you.” It was so beautiful. If you can touch someone’s life, even just a little bit, that’s amazing.

I know many gay books from Colombia, but none of them are about women. I wanted to say out loud that these were lesbian women. In a broader sense, I want people to realize that female writers and female characters are interesting enough. The male characters in my book have important roles in the novel, but they never speak. They don’t have a personal voice—much like women were denied for a very long time. This is a political point. I hope my book contributes in that way, to show that female characters have their own voices and stories.

Creative Writing and Academia

In academic writing, you have to be very concise, and I’m not very good with that. I crave freedom and expression.

Writing this novel helped me say serious things—political statements that might be dangerous to say in other contexts—through different voices: that of an old lady, a middle-aged person, or a teenager. This is the freedom of creative writing.

Academia familiarized me with the publishing process, how to do research, and how to structure my time in order to write consistently and systematically. I wrote for five hours every day.

I also wanted to practice some of the things I learned in graduate school as a literary scholar. For instance, using four characters to tell the same story from different perspectives is a characteristic of Modernist literature that I wanted to try. I also wanted to incorporate the idea of how memory changes, a concept I worked with a lot during my Masters and PhD. I wanted to show how everything has a domino effect: when one person makes a decision, it not only affects them, but the entire family.

Personal Growth

I once did the Camino de Santiago in Spain, which involved thirty days of walking 852 kilometers from east to west, crossing small towns and meeting people from around the world. The publishing process felt similar: it’s a very long process, but it makes for a great journey.

Famous authors say that writing is therapeutic, and it’s true. It has helped me resolve things from my past and say the things I needed to say.

The first time I shared my work with others, it was frightening—I felt so vulnerable, totally naked, like I was baring my soul—but I needed to write this. Sometimes I feel like I’m not good enough or I feel scared to share my ideas out of fear of looking stupid, but writing this book was like saying, “This is what I can do. This is what I have to offer.” And I love that. Yes, this is my first novel and it might have plenty of mistakes, but I feel like a better person now because I believe more in my own abilities and have friends who support me. That’s huge.

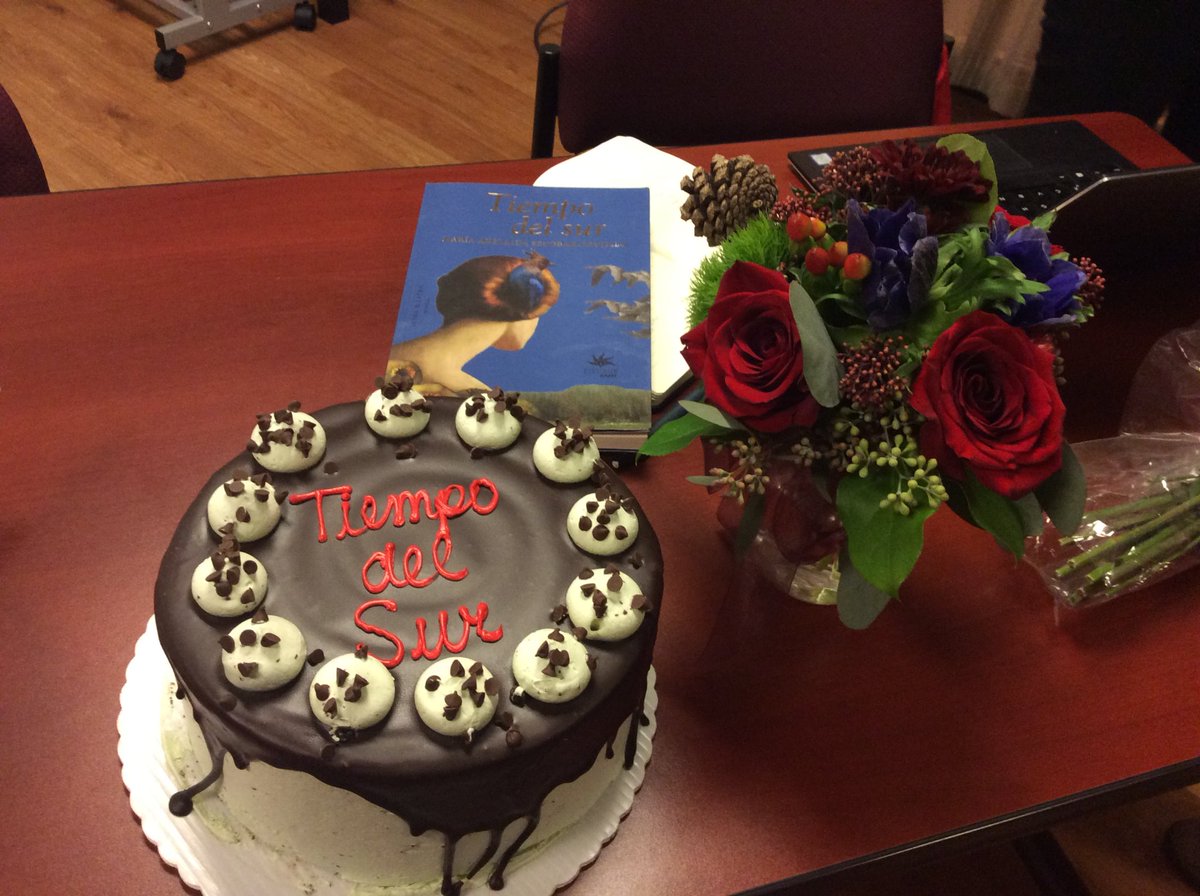

Copy of Tiempo del sur alongside cake and flowers at the FHIS book launch.

Connection

The most important thing for me is connection. If people can connect personally and emotionally with my characters and feel compassion for them, that would make me very, very happy. That kind of gift is priceless. I don’t need to ask for anything else.

People are very important. To make contact is important. That is also why I love teaching so much.

For me, academia is most valuable when it’s connected to reality. That’s what I love about the Department of French, Hispanic and Italian Studies: it’s very active.

Initiatives like Maria Carbonetti’s Spanish for Community, Brianne Orr-Álvarez’s FHIS Learning Centre, or Stephanie Spacciante’s Go Global study abroad program—these help students relate to academic content in a very personal way.

It makes me feel emotional to think of how lucky I am to have colleagues and friends who celebrate my successes. I wasn’t expecting this, since my book is a work of fiction and not research. To belong in a workplace that is such a dream to be in and to have such nice colleagues—what else do I need? I am very, very lucky.

Learn more about Dr. María Adelaida Escobar-Trujillo and her novel Tiempo del sur.