Dr. Tamara Mitchell, Assistant Professor of Spanish, provides a recap of the conference titled “Listening with the Eyes: The Sounds of Latin American Literature” which took place on October 14-15, 2022.

“Attending to the sonic in literature opens the possibility of challenging the hegemony of lettered practices in generative ways.”

The Significance of Aurality in Latin American Literature

In Latin America, a region with a protracted history of colonialism and interventionism, oral cultures and ways of knowing have been devalued in favour of lettered literacy. These values and attitudes have overwhelmingly affected marginalized communities, and particularly Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples. Attending to the sonic in literature opens the possibility of challenging the hegemony of lettered practices in generative ways. Beyond this decolonial potential, reading with an ear to the sonic may take many forms and have a number of outcomes and effects. As one example, literary aurality may constitute an ethical gesture, a way of listening to the other while writing (on the part of the author) and reading (on the part of the reader).

The “Listening with the Eyes: The Sounds of Latin American Literature Conference” was organized around the idea of Latin American literary works that invite and incite the reader to listen. This can occur through a variety of formal or thematic means, for instance, from the consistent deployment of church bells as a literary motif in a work about Catholicism, or by formally imitating a certain style of music (intermediality). Such strategies make the reader’s (internal) ear perk up and engage listening as an additional layer of reading.

One might envision many possible outcomes of this embodied and multisensorial mode of listening. In the example of the church bells, scholars like Alain Corbin have observed how the peels of bells served to standardize time, structure social relationships, mark the boundaries of village territories, and consecrate (or deny recognition of) national or religious celebrations. Recognizing the profound symbolic, political, and social resonances (pun intended) of the bell, an author might incorporate—or silence—the familiar tolls of a bell to powerful effect in a work of literature.

Topics Covered

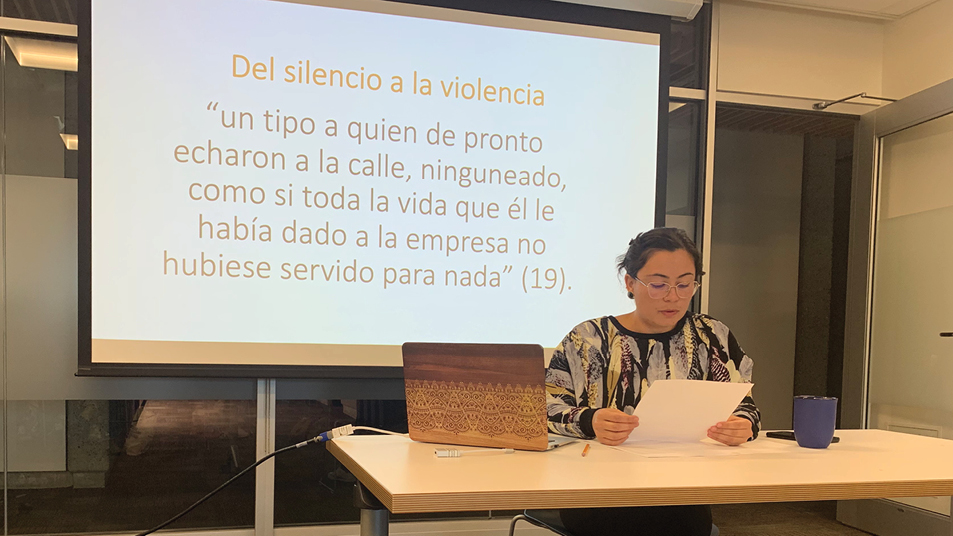

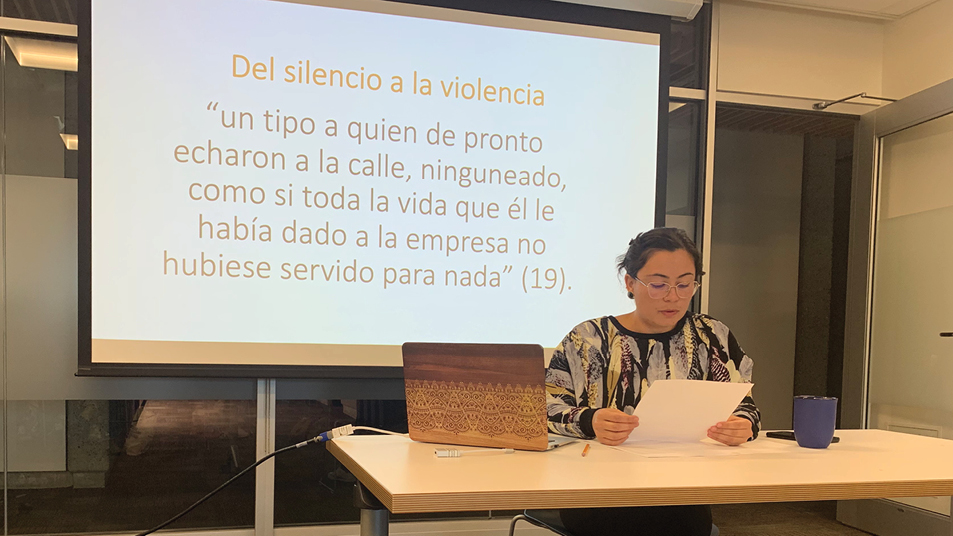

Pamela Zamora, PhD Student of Spanish, delivers a talk on the role of sound and music in a postwar novel by Honduran author Horacio Castellanos Moya.

“Presentations ranged from a sonically attuned revaluation of a much-studied ancient Indigenous text, to reflections on literary echoes of the present-day migrant crisis at the Mexico-U.S. border.”

The conference and workshop served as a first step towards a special issue on Latin American literary aurality, which has been preliminarily accepted for publication with Revista de Estudios Hispánicos. My co-organizer, Prof. Amanda M. Smith of the University of California Santa Cruz, and I hoped that, beyond serving as an impetus to make progress on their articles, contributors would receive useful feedback on their in-progress work.

With five in-person talks and three virtual panels at a Zoom workshop, the presentations for “Listening with the Eyes” ranged from a sonically attuned revaluation of a much-studied ancient Indigenous text (El Popol Wuj), to reflections on literary echoes of the present-day migrant crisis at the Mexico-U.S. border. Presenters discussed works from Pre-Conquest Mesoamerica, Argentina, Colombia, Cuba, El Salvador, Mexico, Peru, the United States, and the ancestral lands of the Wayuu people.

Below is a summary of the presentations and workshops.

Day 1:

- Azucena Hernández Ramírez (Arizona State University) read Justo Sierra’s chronicle, En tierra yankee (Notas a todo vapor) (1895), to evaluate uneven processes of modernization between Mexico and the United States by considering the sounds and silences perceived from a train car crossing the Mexican desert before entering the industrialized United States.

- Carlos Abreu Mendoza (Texas State University) proposed the term “the audible sublime” to conceptualize writers’ (often failed) attempts to comprehend and represent natural and human geographies in the early Latin American nation state.

- In an examination of the documentary Somos hombres cascabel (2018, dir. Jorge Mario Suárez) and poetry by Wayuu author Livio Suárez Urariyuu, Daniel Hernández (Wesleyan University) and Joseph Wager (Stanford University) considered how Colombian windfarms that produce “clean” wind energy are dissonant with Wayuu cosmology and soundscapes.

Day 2:

- Luis Calí (Música Maya Aj), Rita M. Palacios (Conestoga College), and Paul M. Worley (Western Carolina University) revisited El Popol Wuj, a foundational Mayan text that contains a wealth of knowledge and the cosmology of the Mayan peoples. Their talk attended to the sonorously performative aspects of the work, with special attention to the role of the q’ojom

- Víctor Sierra Matute (Baruch College, CUNY) discussed the Afro-Peruvian mystic Úrsula de Jesús, whose Diario espiritual (1661) turns to the sonic sphere to describe her ecstatic experiences in a 17th-century convent and to characterize Purgatory as an aural space.

- Based on extensive archival work at the Harry Ransom Center, Ana Cecilia Calle (Wake Forest University) detailed how cumbias are erased or marginalized in Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez’s oeuvre. She interprets this erasure as a form of “distant listening” that others racialized sounds and allows the narrator to conceive of himself as a lettered subject.

- Attuning to the sounds of violence, popular culture, and spectacularized news media in Horacio Castellanos Moya’s Baile con serpientes (1996), Pamela Zamora Quesada (University of British Columbia) showed how the novel’s sonic register indexes exclusion and becomes a means of disruption in the Central American postwar.

- Anke Birkenmaier (Indiana University) examined the resonances between the sonority of modernist authors like Virginia Woolf and Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive (2019) to identify a sort of literary activism in Luiselli’s aural narrative.

Lastly, I was particularly excited that the conference overlapped with my graduate seminar, “SPAN590: La narrativa sonora: El sonido en la literatura contemporánea de Latinoamérica.” Given the thematic parallels between the course content and the conference, my students were tasked with selecting one of the texts that was presented during the conference, reading that work and attending the respective talk, and then composing a post on our course blog reflecting on the literary work and presentation. My hope was that the SPAN590 students were able to gain insight into the analysis of sonic literature, as well as to meet vibrant thinkers active in the field of literary sound studies. Reading their thoughtful blog posts has been a gratifying postscript to the conference.

Acknowledgements

I was extremely grateful for the collaboration of my co-organizer, Professor Amanda M. Smith of the University of California, Santa Cruz, as well as the support of the Department of French, Hispanic and Italian Studies (FHIS), particularly Raquel Costa and Celine Diaz. We received funding from the Faculty of Arts (SSHRC Exchange) and FHIS (Dorothy Dallas Fund), which allowed for snacks and meals throughout both days and offset the cost of accommodations for the visiting speakers.

Most importantly, I’m grateful to the presenters and attendees for their enthusiastic and engaged participation in the event. The audience posed thoughtful and generous questions that invited conversation and pushed the speakers in fruitful ways, and the presenters delivered dynamic talks that got the FHIS community thinking about sound and listening in/to literature.