Dr. Karen O’Regan, former PhD student of Hispanic Studies, explores how narratives of the Hispanic Caribbean diasporas invite readers to contemplate other ways of being in the world—ways that value difference and open relations over bounded identities. She also describes what her graduate experience has been like at UBC.

“These texts demand a witnessing of the injustices suffered by many peoples and the healing that can occur when communities privilege connections with others over a politics of inclusion and exclusion.”

Part 1: Research

Challenging traditional notions of community

Dr. Karen O'Regan, former PhD student of Hispanic Studies

In Vancouver, you won’t have to go far to find someone whose community doesn’t claim a national or cultural identity. I’ve heard people say, “I’m Cuban, but the people I spend time with don’t identify as Cuban or Canadian. I don’t know what we are.”

Most of us belong to more than one community that can be categorized according to citizenship, culture, language, religion, race, class, gender, or sexuality; however, some people also live in communities that can’t be identified.

The cultural inter-contaminations so creatively evoked in Caribbean diasporic literature make us wonder whether all communities claim an identity.

I study how contemporary writers from Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico—who spend much of their lives outside the Caribbean—narrate life in their diasporic communities.

Two questions guide my research:

- How do writers of Hispanic Caribbean diasporas write about community?

- Do their diasporic voices evoke a longing for rootedness, or do they reimagine the idea of belonging in a transborder era?

To answer my research questions, I study narratives that challenge traditional notions of community. I look at the way writers play with language to create characters whose ties with others are more important than naming these relationships. That is, I investigate the linguistic and literary tools that they use to engage readers in a dialogue as to the meaning of community.

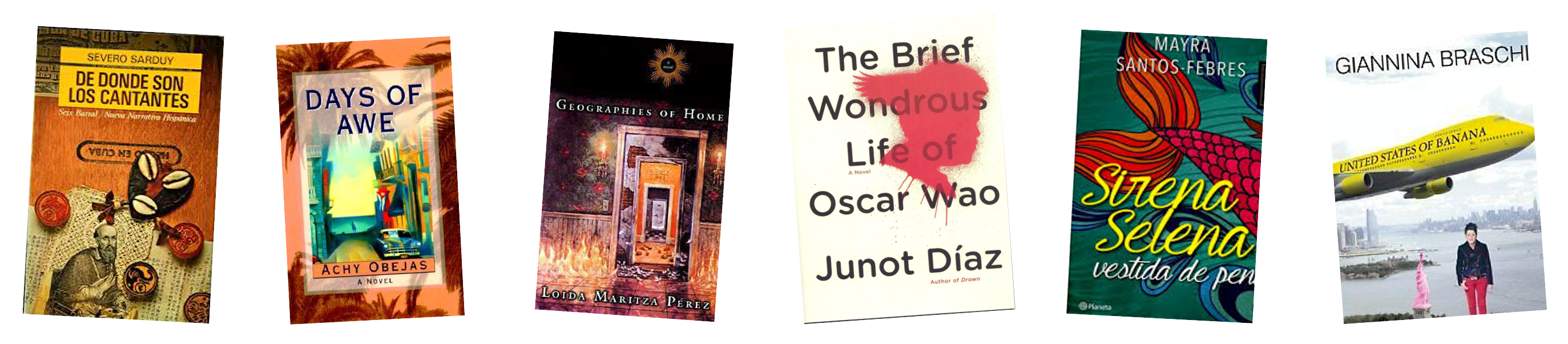

Left to right: De dónde son los cantantes by Severo Sarduy, Days of Awe by Achy Obejas, Geographies of Home by Loida Maritza Pérez, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Díaz, Sirena Selena by Mayra Santos-Febres, and United States of Banana by Giannina Braschi.

Privileging connection over a politics of inclusion and exclusion

Narratives of the Hispanic Caribbean diasporas invite readers to contemplate other ways of being in the world—ways that value difference and open relations over bounded identities. Such writing and reading reimagines our relationality.

My family has lived in many places where we encountered people from different backgrounds living in communities that escaped categorization. In Trinidad, for instance, our community was made up of individuals from various Caribbean islands, India, North America, England, and China.

When I got typhoid from a public pool, the community demanded cleaner water for the local school children. Our commonality at that time emerged from the desire to avoid a serious health issue. We didn’t ignore our differences—they were a given—but we prioritized our well-being over the need for a common identity.

We see examples of such linkages during the Covid-19 pandemic. The appreciation we all feel for our front-line workers has connected individuals across socio-cultural and political borders. I am awed by the sights and sounds of people around the world banging pots on their balconies in support of others. Such spontaneous gestures of compassion indicate a solidarity that is as creative as it is healing!

All social groups have the right to assume a common identity (or non-identity) with which to challenge discourses that persist in capturing their voices. These texts demand a witnessing of the injustices suffered by many peoples and the healing that can occur when communities privilege connections with others over a politics of inclusion and exclusion.

Part 2: Graduate Student Experience

Research in La Habana, Cuba (2018)

Why did you choose UBC to pursue your studies?

I had taken a number of undergraduate courses at UBC, so I knew that the Department of French, Hispanic and Italian Studies had dynamic undergraduate and graduate programs. Friends and students in Hispanic Studies would talk about their stimulating courses, conferences, and trips abroad. I was particularly excited about the professors I would be working with, as I would have the opportunity to receive expert guidance in my chosen field.

I am profoundly grateful for all that I have received from the Department of French, Hispanic and Italian Studies. So many opportunities!

What was it like working with your graduate supervisor?

Dr. Alessandra Santos has been an unfailing source of support throughout my academic career. I chose her as my PhD thesis supervisor for her area of expertise and because I knew she would encourage my voice, while insisting I meet the highest standards of academic scholarship.

Her mentorship consists of an ideal combination of generosity and firmness. Whether advising me in her office, on a ferry, or via email from Brazil or elsewhere, she has provided invaluable counsel in the research process. The best thing about working with Dr. Santos is the compassion with which she approaches her interactions with others and her genuine interest in her students’ progress.

She and my committee members, Dr. Beauchesne and Dr. Beasley-Murray, invest a great deal of time in fostering a strong community of scholars at UBC. They will wake up at all hours to chair conference panels, meet students in a café on weekends to discuss their projects, and create open seminars that promote engagement with communities in Canada and abroad.

What advice would you give to those who are discerning whether graduate school is for them?

If this is your passion, pursue it!

I have always enjoyed studying literature and sharing ideas with others in literature courses or more informal settings. However, there weren’t enough hours in the day for graduate studies while I was raising my son and teaching full time. When he was older, I was able to apply for graduate school and learn from many inspiring encounters in literary studies.

What are your career goals?

I plan on studying literature with individuals of various communities, with whom I hope to contribute to research and writing in my field.

Interested in Graduate Studies?

Learn more about the MA and PhD in French or Hispanic Studies:

fhis.ubc.ca/graduate

Applications:

Deadline for the September 2021 and January 2022 intake is January 31, 2021.