Dr. Sima Godfrey, Associate Professor of French Studies at UBC, explores the concept of ‘collective forgetting’ in her research on France’s role in the Crimean War. She is a recipient of the Wall Scholars Research Award for 2019-2020.

Dr. Sima Godfrey, Associate Professor French Studies at UBC

“While there has been a great deal of work done in recent years on ‘collective memory’, the French status of the Crimean War raises important questions about ‘collective forgetting’.”

Tell us about your research.

Despite the many years I have studied French literature and cultural history of the 1850s, I discovered serendipitously, to my embarrassment, that I knew virtually nothing about the role of the French during the Crimean War (1854-1856).

I was fully aware of Britain’s participation in the war (“Charge of the Light Brigade”, Florence Nightingale), as well as Russia’s (Tolstoy’s Sebastopol Sketches, etc.), but I was ignorant of what the French were doing, or why they were in Crimea in the first place.

How did I miss a three-year war that the French had fought and won — in fact, the only war they had won in the 19th century?

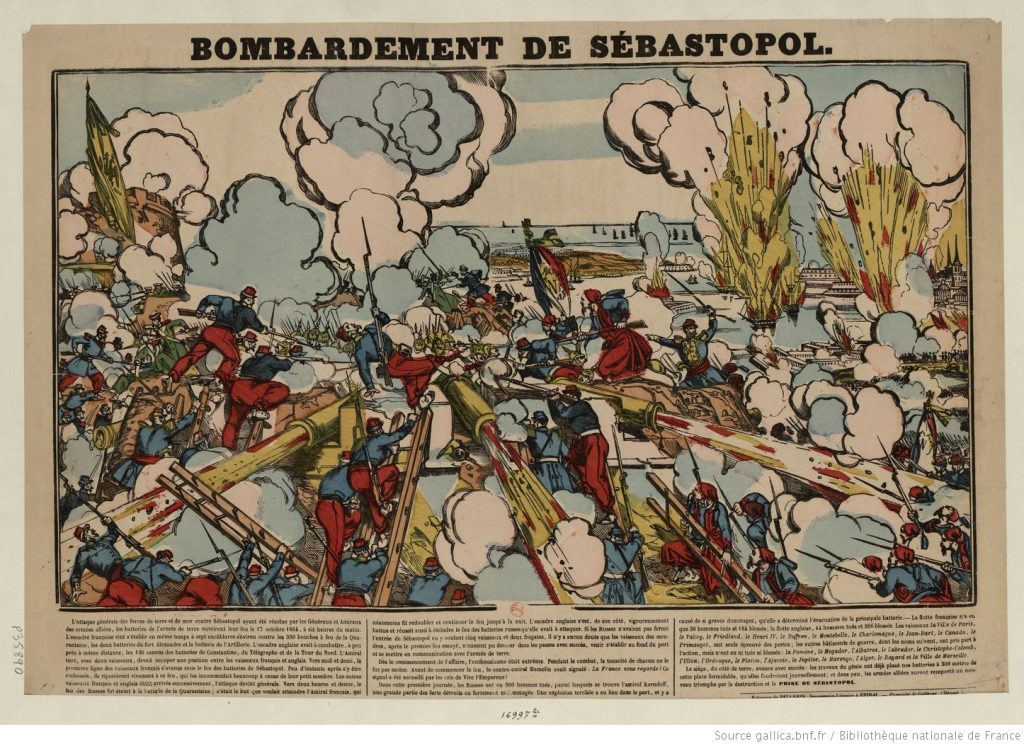

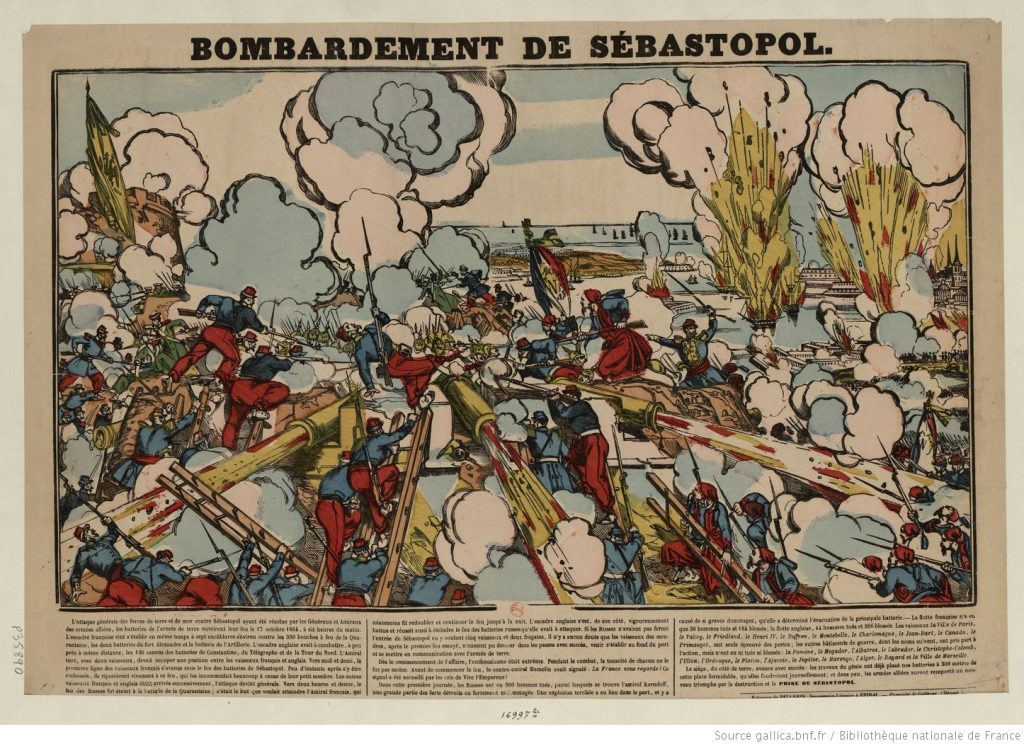

If I knew so little about France’s participation, I soon realised, it was not just because of my woeful ignorance. The event did not appear in any of my readings from that period, nor in any of the secondary readings. It was not featured in any of the canonical novels, short stories or poetry of the second half of the 19th century, and yet, it was on the front pages of every major French newspaper for two full years. It was commemorated in huge official paintings commissioned by the state; it inspired countless caricatures, articles and pictures in the illustrated press; it penetrated popular culture in the form of equestrian spectacles, vaudevilles, illustrated game boards, painted dishes and even embroidered handkerchiefs — but it remained invisible in elite culture.

My research project, titled “La Guerre de Crimée n’aura pas lieu: Crimea, the Invisible War”, thus looks at how the Crimean War was/is remembered in France across a spectrum of media and genres, and how it was/is forgotten.

Painting by Horace Vernet in 1858 showing General MacMahon next to a Zuavo soldier at the top of the Malakoff. This is the moment of the famous declaration: “J’y suis, j’y reste!”

What questions do you seek to address?

While there has been a great deal of work done in recent years on ‘collective memory’, the French status of the Crimean War raises important questions about ‘collective forgetting’.

Not a calculated repression of regrettable, misguided, or heinous events in the past, but l’oubli, that is, “forgetting”. What does it mean that a war can disappear from cultural memory? What does it mean that this particular war disappeared from French cultural memory? Given the prominence of the Crimean War in British national mythology, what does it mean that this war is nothing more than a dusty footnote, if even that, in French national mythology? How is it that French commemorations of this particular war — in which 100,000 Frenchmen were killed — are so few and so discreet so as to be overlooked?

By comparison, the British memory of that war — to which they sent fewer men than the French lost — quickly spread and implanted itself across the entire Empire. That is why we have an “Alma Street” and a “Balaclava Street” right here in Vancouver. That is why we wear cardigans (Lord Cardigan, commander of the infamous Light Brigade) that sometimes have raglan sleeves (Lord Raglan, commander of the British troops in Crimea). Which lead me to question: what is the general nature of commemoration? And what role does literature play in the commemoration of a war?

In his novel, Les Misérables, Victor Hugo made a minor uprising in Paris in June 1832 so memorable that it went to Broadway. Hugo also wrote an angry poem condemning the French general who led the French into Crimea and, in a speech, later denounced the war as a disastrous self-aggrandizing gesture by Emperor Napoleon. But neither of these short texts fixed the war into the cultural radar. In Britain, it took only one poem, “The Charge of the Light Brigade” by Alfred Tennyson, to inscribe it indelibly. Did the Crimean war need its own novel?

What makes this topic compelling?

What has made this project both so compelling and so challenging is that, as a literary historian, I am writing about something that is not there.

It is something of a bagel exercise: there is a hole in the middle surrounded by lots of tantalizing “dough”. This project doesn’t describe representations of the war in literature or national memory, but rather their absence. Then comes the big question: what do we make of this absence? What might it mean? More generally, what insights can we derive from this example of national memory and collective forgetting?

How does your project tackle these questions?

Bombardement de Sébastopol (1854-1855). Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

In order to address such questions, one has to look at a variety of disciplines and the ways they intersect: literary history, art history, military history, even theatre history, plus sociology, politics, material culture and psychology.

To this end, I am looking at canonical and popular writings of the second half of the 19th-century in France (and also Quebec, where one of the major poets wrote proud, patriotic poems). I am reading memoirs and letters of French officers, soldiers and army chaplains. I am looking at grand epic paintings of the war, lithographs and popular caricatures in the illustrated press, as well as photographs — this was, in fact, the first war that was photographed.

In my examination of reports and articles from the press, I have looked at newspapers and journals that also contained serialized novels and poems. And — most fun, perhaps — I have been studying and collecting contemporary material objects that commemorated the war: board games, china dishes with battle illustrations, perfume bottles, embroidered handkerchiefs, etc.

Here is an article I wrote that provides an introduction to this project and some of the questions it raises: “La Guerre de Crimée n’aura pas lieu”, French Cultural Studies, 2016, Vol. 27(1) 3–19.

Dr. Sima Godfrey was selected as a Peter Wall Institute Wall Scholar for 2019-2020. The Wall Scholars Research Award is available to UBC Faculty members to spend one year in residence at the Institute in a collaborative, interdisciplinary environment. Learn more.